This is a condensed version of a speech that Amazon Vice President and Chief Technology Officer Dr. Werner Vogels gave AI for a good global summit in July 2025 in Geneva.

In January 2007, my mentor, friend and colleague -computer researcher Jim Gray, a Turing prize, disappeared often as the father of modern database systems while sailing solo to the Farallon Islands at San Francisco. Despite implementing every conceivable technological resource, from relocating government satellites to mobilizing thousands of recruits through Amazon’s mechanical Turk to analyze satellite images, we never found him. If we had today’s AI resources, would the result have been different? Perhaps. There are things that we can do now that we certainly couldn’t do in 2007.

While Jim’s friends were able to use their private sector relationships and state approvals to access real-time satellite data, most vulnerable communities remain invisible in our digital soil presentations. Haiti -Earth Quake of 2010 made this painfully clear. International rescue teams arrived in Port-Au-Prince to find a city that for all practical purposes non-mapped. Emergency persons had GPS coordinates but could not navigate because the cards they had could not distinguish between alleys and major ways or locate critical infrastructure such as hospitals and shelters.

The data division

The situation in Haiti is not unique. Consider Makoko, a society in Lagos, Nigeria, it is home to more than 300,000 people living at the positions of Lagos Lagoon. On most maps this whole society appears as an empty blue place. These people are effectively invisible and cannot access basic services because they are not found in our spatial data models.

The reason for this omission is simple: Most cards are created for commercial purposes, not humanitarian needs. We carefully map shopping districts in larger cities, but leave large shards of developing countries that are unknown. This creates what I call “Data Divide”, a difference in data approach that mirrors and aggravates existing social inequalities. When we only map what is profitable, we immortalize these inequalities and leave the most vulnerable communities exposed.

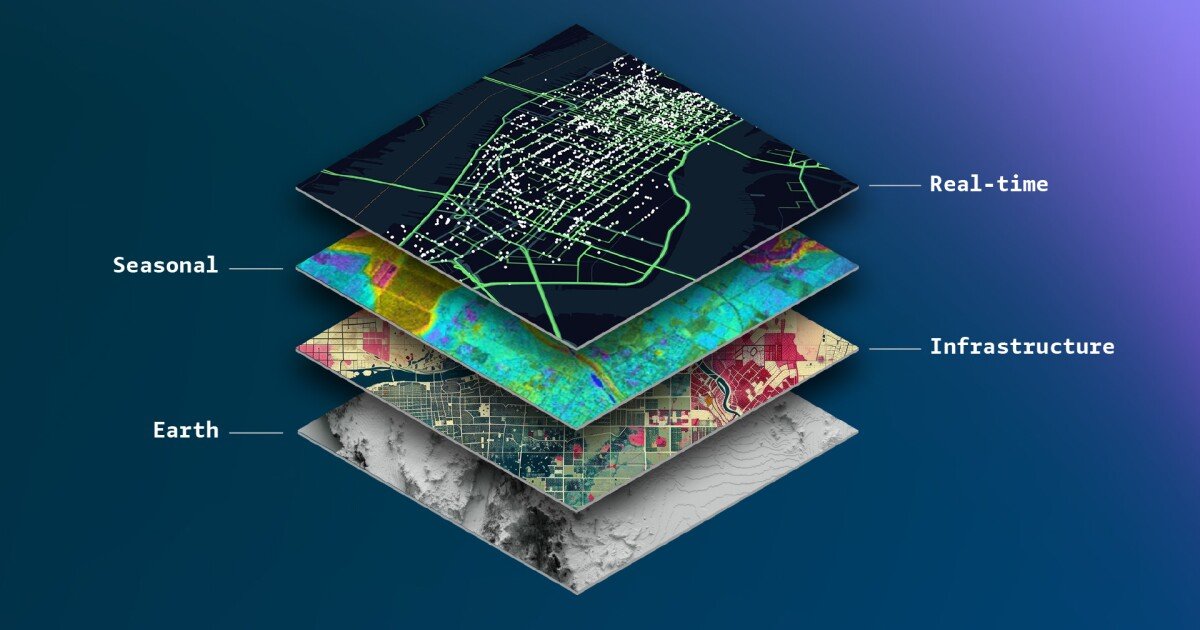

Now, if you think of cards there is not just a map of the earth. The moment you have a traditional card in your hand it is outdated. Effective maps are multilayered systems that work across different time scales.

First, there is the soil layer, the slowly changing geographical features that remain constant over decades or centuries. The Himalayas or the Amazon Basin will not move soon. Then there is the infrastructure layer – roads, bridges and buildings that develop over years. Next comes the seasonal layer that tracks changes in vegetation, water level and other environmental factors that change with the seasons. Finally, there is the real -time stroke, a constant fluctuating flow of data on human activity, weather patterns and emergencies.

Humanitarian mapping should integrate all of these layers. During a flood, for example, we need real -time data on the water level (real -time layers), historical flood patterns (seasonal layers), existing drainage infrastructure (infrastructure layer) and underlying topography (soil layer). Combining these data flows requires sophisticated AI models that can handle multiple data types and temporal scales.

Democratization of land data

The good news is that the tools for data collection have become much more accessible. The number of earth observation satellites has exploded from approx. 150 in 2008 to over 10,000 today. These satellites not only offer high resolution images, but advanced sensors such as multispectral image men, radar and Lidar.

In the wake of the Haiti -Earth quake was approx. 600 members of the OpenStreetMap community are able to create the first reliable crisis card within 48 hours. It only took two days to go from non -short -to -mapped. This crowddsourced card was the standard navigation tool for any major equivalent organization, from the UN to the US Marine Corps. OpenStreetMap has since evolved into a global platform for collaborative mapping, with Spinoffs as Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (Hot) and missing cards that specifically focus on crisis.

Drones have emerged as a powerful supplement to satellites filling holes where satellite images are insufficient or too expensive. Mapping Makoko project trained local residents to pilot drones and map their community. This initiative did more than create a map; It authorized the residents with a tool for political advocacy and demonstrated the power of democratized data collection.

While satellites and drones provide macro-level data, mobile devices and Internet-of-things (IoT) sensors offer granular information in real time. With over eight billion mobile devices globally, we have an unprecedented option for crowddsourced data collection. In Southeast Asia, the Grab app (a super-app that delivers everything from riding that comes to food delivery) has detailed maps of previously unalted areas simply by tracking the routes for its drivers who are familiar with neighborhoods, allegations and unmarked homes. Similarly, India’s Namma Yatri app connects Auto-Rickshaw drivers with passengers while generating accurate street maps over informal settlements.

IoT sensors embedded in infrastructure provides another layer of real-time data. Environmental sensors that track air quality, water level or seismic activity can give birth directly in mapping systems, creating a dynamic representation of a society’s current state.

Building with open data

During a recent visit to Rwanda, I first saw how data -driven mapping can transform the delivery of healthcare. Rwanda Health Intelligence Center uses real -time data to track health utilization across the country. By combining this with geospatial data, they have calculated the maximum walking distance for pregnant women to reach a health center. This data informs directly where to build new facilities and optimize resource allocation.

Another inspiring example is the Ocean Cleanup Project, which aims to remove 90% of Ocean Plastic by 2040. They have developed a river model using drones, AI analysis and GPS-labeled Dummy plastic to predict plastic flow patterns. This data-driven approach allows them to place their cleanup systems in the most effective places, while AI-driven cameras on bridges identify different types of plastic in real time.

The large amount of geospatial data – hundreds of petabytes from satellites, drones and IoT sensors – requires robust infrastructure. Cloud platforms like the Amazon S3, which processes over a quadrillion request every year, allows you to store and process this data in scale. Our Open Data Sponsorship Program Removes additional barriers by covering the cost of high-value public data sets, including OpenStreetMap, Sentinel-2 images and various environmental sensory data.

Planetary problem solving machine

The combination of open data, advanced AI models and Sky Infrastructure creates what I call a planetary problem solving machine. This trio can tackle challenges that were previously indispensable. Open data ensures transparency and verifiableness, while AI extracts insight that it would be impossible for humans to distinguish.

When we have data that can save lives or protect the environment, it is morally unjustifiable to keep it private. The United Nations 17 Sustainable Development [HE1] Goals all depend on geospatial data. Whether it is to end poverty, achieve food security or fight climate change, any measure requires placement -based data to measure progress and guide interventions.

The question for all of us is what data do we have that can be useful to others? And more importantly, what data can we open up? If we do not act, we risk perpetuating a world where the most vulnerable remains invisible where disasters are worsened by lack of information and where progress is only measured in places that are profitable.

It is for this exact reason that by 2024 I launched the now GO Build CTO scholarship. To bring together technology leaders from non-profit and social good organizations working to tackle climate change, disaster management, healthcare availability, food security, education and pair them with experts at Amazon, AWS and beyond. I have seen first -hand how these fellows use data to solve the world’s most difficult problems, whether it is to measure crops, connect excess food with charities and families or pilot drones in conflict areas, none of which are possible without maps.

Cards have always been more than navigation tools: they are instruments for power. In the digital age, they become tools for justice, healthcare and environmental protection. By making the invisible visible, we can create a more just world.

Now go up.