AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) policies give customers fine-grained control over who has access to which resources in the Amazon Web Services (AWS) Cloud. This control helps customers enforce the principle of least privilege by granting only the necessary permissions to perform certain tasks. In practice, however, it requires customers to understand what permissions are necessary for their applications to function, which can become a challenge as the scope of the applications grows.

To help customers understand what permissions are not necessary, we launched the IAM Access Analyzer unused access findings at the 2023 re:Invent conference. IAM Access Analyzer Analyzes your AWS accounts to identify unused access and creates a centralized dashboard to report its findings. The results highlight unused roles and unused access keys and passwords for IAM users. For active IAM roles and users, the results provide visibility into unused services and actions.

To take this service a step further, in June 2024 we launched recommendations to refine unused permissions in Access Analyzer. This feature recommends a refinement of the customer’s native IAM policies that preserves the policy structure while removing the unused permissions. The recommendations not only simplify the removal of unused permissions, but also help customers implement the principle of least privilege for fine-grained permissions.

In this post, we discuss how Access Analyzer policy recommendations suggest policy adjustments based on unused permissions, completing the circle from monitoring overly permissive policies to refining them.

Policy recommendation in practice

Let’s dive into an example to see how policy recommendation works. Assume that you have the following IAM policy associated with an IAM role MyRole:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"lambda:AddPermission",

"lambda:GetFunctionConfiguration",

"lambda:UpdateFunctionConfiguration",

"lambda:UpdateFunctionCode",

"lambda:CreateFunction",

"lambda:DeleteFunction",

"lambda:ListVersionsByFunction",

"lambda:GetFunction",

"lambda:Invoke*"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:my-lambda"

},

{

"Effect" : "Allow",

"Action" : [

"s3:Get*",

"s3:List*"

],

"Resource" : "*"

}

]

}

The above policy has two policy statements:

- The first statement allows actions on a function in AWS Lambda, an AWS offering that provides function execution as a service. The allowed actions are specified by specifying individual actions as well as via the wildcard string lambda:Invoke*which allows all actions starting with Invocation in AWS Lambda, such as lambda:InvokeFunction.

- The second statement allows operations on any Amazon Simple Storage Service (S3) bucket. Actions are specified by two wildcard strings, which indicate that the statement allows actions starting with Get gold List in Amazon S3.

Enabling Access Analyzer for Unused Findings will give you a list of results, each detailing the unused action-level permissions for specific roles. If Access Analyzer e.g. finds any AWS Lambda or Amazon S3 actions that are allowed but not used for the role with the above policy attached, it will show them as unused permissions.

The unused permissions define a list of actions that are allowed by the IAM policy but not used by the role. These actions are specific to one namespacea set of resources clustered together and shielded from other namespaces to improve security. Here is an example in Json format showing unused permissions found for MyRole with the policy we attached earlier:

[

{

"serviceNamespace": "lambda",

"actions": [

"UpdateFunctionCode",

"GetFunction",

"ListVersionsByFunction",

"UpdateFunctionConfiguration",

"CreateFunction",

"DeleteFunction",

"GetFunctionConfiguration",

"AddPermission"

]

},

{

"serviceNamespace": "s3",

"actions": [

"GetBucketLocation",

"GetBucketWebsite",

"GetBucketPolicyStatus",

"GetAccelerateConfiguration",

"GetBucketPolicy",

"GetBucketRequestPayment",

"GetReplicationConfiguration",

"GetBucketLogging",

"GetBucketObjectLockConfiguration",

"GetBucketNotification",

"GetLifecycleConfiguration",

"GetAnalyticsConfiguration",

"GetBucketCORS",

"GetInventoryConfiguration",

"GetBucketPublicAccessBlock",

"GetEncryptionConfiguration",

"GetBucketAcl",

"GetBucketVersioning",

"GetBucketOwnershipControls",

"GetBucketTagging",

"GetIntelligentTieringConfiguration",

"GetMetricsConfiguration"

]

}

]

This example shows actions that are not used in AWS Lambda and Amazon S3, but are allowed by the policy we specified earlier.

How could you refine the original policy to remove the unused permissions and gain fewer privileges? One option is manual analysis. You can imagine the following process:

- Find the statements that allow unused permissions;

- Remove individual actions from these statements by referring to unused permissions.

However, this process can be prone to errors when dealing with large policies and long lists of unused permissions. Also, when there are wildcard strings in a policy, removing unused permissions from them requires careful consideration of what actions should replace the wildcard strings.

Policy recommendation makes this adjustment automatic for customers!

The policy below is one that Access Analyzer recommends after removing the unused actions from the policy above (the figure also shows the differences between the original and revised policies):

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement" : [

{

"Effect" : "Allow",

"Action" : [

- "lambda:AddPermission",

- "lambda:GetFunctionConfiguration",

- "lambda:UpdateFunctionConfiguration",

- "lambda:UpdateFunctionCode",

- "lambda:CreateFunction",

- "lambda:DeleteFunction",

- "lambda:ListVersionsByFunction",

- "lambda:GetFunction",

"lambda:Invoke*"

],

"Resource" : "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:my-lambda"

},

{

"Effect" : "Allow",

"Action" : [

- "s3:Get*",

+ "s3:GetAccess*",

+ "s3:GetAccountPublicAccessBlock",

+ "s3:GetDataAccess",

+ "s3:GetJobTagging",

+ "s3:GetMulti*",

+ "s3:GetObject*",

+ "s3:GetStorage*",

"s3:List*"

],

"Resource" : "*"

}

]

}

Let’s take a look at what’s changed for each policy statement.

For the first statement, policy recommendation removes all individually listed actions (e.g. lambda:AddPermission), as they appear in unused permissions. Because none of the unused permissions start with lambda: Invocationomits the recommendation lambda:Invoke* untouched.

For the second statement, let’s focus on what happens to the wildcard s3: Few*which appears from the original policy. There are many actions that can start with s3: Fewbut only some of them appear in the unused permissions. Therefore, s3: Few* cannot simply be removed from politics. Instead, it replaces the recommended policy s3: Few* with seven actions to start with s3: Few but are not reported as unused.

Some of these actions (e.g. s3:GetJobTagging) are individual, while others contain wildcards (e.g. s3:GetAccess* and s3:GetObject*). A way to replace manually s3: Few* in the revised policy would be to list all the actions that start with s3: Few except the unused ones. However, this would result in an unwieldy policy as there are more than 50 actions to start with s3: Few.

Instead, policy recommendations identify ways to use wildcards to collapse multiple actions that print actions such as s3:GetAccess* gold s3:GetMulti*. Thanks to these wildcards, the recommended policy is concise but still allows all actions starting with s3: Few that are not reported as unused.

How do we decide where to place a wildcard in the newly generated wildcard actions? In the next section, we’ll dive deep into how policy recommendation generalizes wildcard actions to allow only those actions that don’t appear in unused permissions.

A deep dive into how actions are generalized

Policy recommendation is governed by the mathematical principle of “least general generalization”—i.e. to find the least permissible change to the recommended policy that still allows all actions allowed by the original policy. This theorem-supported approach guarantees that the changed policy still allows it everything and only the permissions granted by the original policy that are not reported as unused.

To implement the least general generalization for unused permissions, we construct a data structure known as a sortwhich is a tree whose nodes span a sequence of tokens corresponding to a path through the tree. In our case, the nodes represent prefixes shared between actions, with a special marker for actions reported in unused permissions. By traversing the sort, we find the shortest sequence of prefixes that do not contain unused actions.

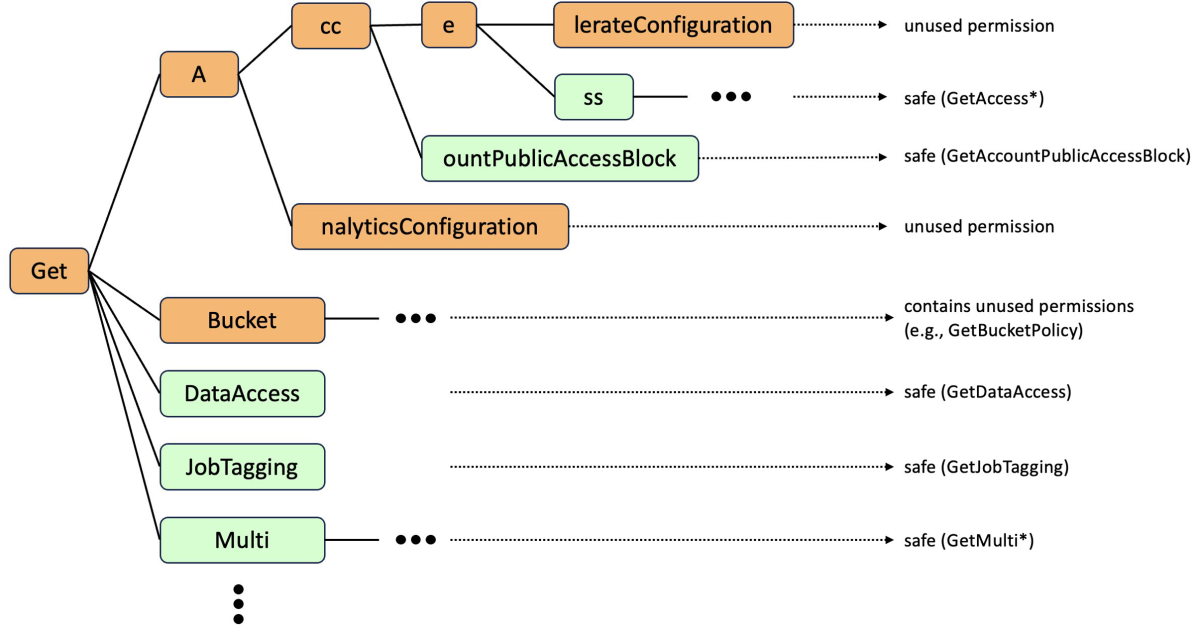

The diagram below shows a simplified sort delineation of actions that replaces S3 Get* wildcards from the original policy (we’ve omitted some actions for clarity):

At a high level, the sort represents prefixes shared by some of the possible actions that start with s3: Few. Its root node represents the prefix Get; child nodes of the root add their prefixes to Get. For example, the named node Multi represents all actions starting with GetMulti.

We say that a node is sure (marked in green in the diagram) if none of the unused actions start with the prefix corresponding to that node; otherwise it is uncertain (indicated in orange). For example the node s3:GetBucket is uncertain because the action s3:GetBucketPolicy is unused. Corresponding to the node pp is safe as there are no unused permissions to start with Get access.

We want our final policies to contain wildcard actions that only correspond to safe nodes, and we want to include enough safe nodes to allow all used actions. We achieve this by selecting the nodes that correspond to the shortest secure prefixes – i.e. nodes that themselves are secure but whose parents are not. As a result, the recommended policy supersedes s3: Few* with the shortest prefixes that do not contain unused permissions, such as s3:GetAccess*, s3:GetMulti* and s3:GetJobTagging.

Together, the shortest safe prefixes form a new policy that, although syntactically similar to the original policy, is the least generalization that results from removing the unused actions. In other words, we have not removed more actions than necessary.

You can find out how to start using policy recommendation with unused access in Access Analyzer. To learn more about the theoretical basis driving policy recommendation, be sure to check out our scientific paper.